Conclusive proof of ‘Black Diaries’ forgery, finally.

By Paul Hyde.

Among the diaries attributed to Roger Casement there is a cash ledger for 1911 which is also part diary. This has been scrutinised by several authors, most closely by Jeffrey Dudgeon, the Belfast researcher who is today the leading forgery denier.

In 2002 Dudgeon published the first edition of his book bearing the title ‘Roger Casement: The Black Diaries – with a study of his background, sexuality and Irish political life’. This substantial volume purported to add rich detail and colour to the already widely established view that the diaries were authentic. Dudgeon was able to present much information about the north of Ireland in relation to Casement and also to provide something missing from other studies – what it was like to be an active homosexual in the North (and elsewhere) a hundred years ago. Dudgeon’s history recipe freely mixes fact with speculation and ‘in-the-know’ innuendo to promote his desired conclusions of authenticity which are guided more by an obvious bias than by impartial analysis. His book, although stylistically challenging and idiosyncratic, has gathered both attention and praise.

A certain sentence on page 285/6 had disappeared.

Dudgeon has never doubted the diaries are genuine and he no doubt believes he has demonstrated their authenticity to the highest degree possible. As the years passed his reputation grew as a veteran crusader who knew ‘the inside story’ and he became an influential expert consulted by authors, academics, journalists, guest speaking at conferences and appearing on the media. Such a success story that by the centenary year of 2016, he produced a second edition to meet steady demand. Then, only two years later in early 2019, he produced a third edition. There was however one small difference in this third edition. A certain sentence on page 285/6 had disappeared. The 27-word sentence, apparently insignificant, had been in print for 17 years but was deleted in 2019. To discover the motive for this unexplained deletion is also to discover its significance for the entire controversy about the diaries. The devil is in the detail we are told so let us look at the detail to find the devil.

The detail concerns an alleged affair between Casement and a young Belfast bank clerk called Millar; Casement did indeed know Millar and his mother through shared friends and acquaintances in Antrim but they had little in common politically. Readers of ‘Anatomy of a lie’ will recall that the widely-believed story fabricated by MI5 agent Major Frank Hall and promoted by Dudgeon is logically demonstrated to be manufactured evidence. The alleged affair features in the 1910 diary and in the 1911 ledger with events located in Belfast and environs. The story also involves a motorcycle owned by Millar in 1911 which vehicle was identified by Hall in 1915 along with the full name of its owner, Joseph Millar Gordon. Hall passed this information to the cabinet meeting on 2 August 1916 to overcome lingering doubts about the expediency of an execution next morning. Hall’s tactic succeeded.

§

In the ledger the following appears dated 3 June:

“Cyril Corbally and his motor bike for Millar £25.0.0″.

Cyril Corbally was a noted croquet player from County Dublin who in 1910 worked at Bishop’s Stortford Golf Club in Essex. In 1910 he acquired a second-hand Triumph motor cycle registered with Essex County Council. In 1911 Corbally sold the machine and in July Millar registered ownership with the same Council.

The sentence is understood to mean that the diarist is paying £25 to Corbally to purchase his motorcycle for Millar. Research has confirmed that £25 is a realistic price in 1911 for a three-year-old Triumph motorcycle; a new machine in 1908 cost around £50. However, as a simple record of a purchase the sentence is suspect because it contains four items of information when two would have been sufficient. It was not necessary to record the vendor’s name, the item bought, the purpose of the transaction and the sum paid. The vendor’s name and the price would have been enough to record the purchase. The extra information – purpose and item bought – is superfluous unless intended for third parties who the diarist knows will read the ledger. In short, the sentence is an artifice.

There are two further references to the alleged transaction in the ledger: on June 8 which reads ‘Carriage of motorbike to dear Millar. 18/3’ and at the end of June ‘Epitome of June A/C Present etc. to others Cyril Corbally…25.0.0.’ Outside the ledger there is no evidence that Casement ever contacted Corbally; nor is there any reference to the purchase of a motorcycle.

§

Here is the sentence which Dudgeon deleted from his third edition of 2019. “It is possible that Millar bought the motor bike from Corbally and that Casement was repaying him as a separate note listing expenditure simply reads ‘Millar 25.0.0′”.

This sentence published by Dudgeon from 2002 to 2019 fatally compromises his overall endeavour to persuade us of authenticity. It signifies serious confusion; he does not know who paid for Millar’s motorcycle. It also signifies that he admits the possibility that Casement did not pay Corbally as alleged in the ledger which therefore would be a forgery. This confusion signals that Dudgeon is unable to make sense of the ledger and consequently has lost faith in his project. He cannot explain why if Millar paid Corbally, the ledger records that Casement also paid Corbally. It is possible that an astute, well-meaning reader alerted Dudgeon to the fatal implications of that sentence but after 17 years it seems improbable that he suddenly discovered the gaffe by himself.

That ‘separate note’ is a single handwritten page in the National Library of Ireland (NLI) described as Rough Financial Notes by Roger Casement (MS 15,138/1/12). It is inscribed on both sides with records of outgoing payments. Many of the ten undated payments record substantial amounts so that Millar’s £25 is not exceptional. The NLI file holds fourteen used cheque books and in many cheque stubs we find comparable payments; but there is no used cheque book for the May/June period. Casement certainly wrote cheques in that period but the used cheque book and dated stubs has disappeared. A stub with Corbally’s name would be conclusive evidence of the Corbally payment but there is no such stub and no used cheque book.

None of the payments are recorded in the ledger; nor do they seem to be in chronological order: the purpose was probably to sum up the amounts paid before leaving for South America in mid-August 1911. The figure of £105 is the cumulative total of 3x£35 quarterly payments to his sister Nina so its date is around the end of June. It is clear that most if not all were made in June and July and one payment to a Belfast friend is confirmed by a July 12 thank-you letter in the NLI file. The list was written in July and updated in August. On the reverse side payment totals are recorded for July and August. With regard to the Millar payment it is a fact that Millar had his twenty-first birthday on 23 June, 1911; however, the suggestion that the money was a birthday gift cannot be confirmed.

The ledger account and the NLI Millar note share several features which deserve attention. It might be coincidence that both refer to an identical sum of money – £25. And both refer to Millar – perhaps another coincidence. Then of course both involve Casement. And the ledger and note are understood to have been written around the same time – June 1911. Lastly, both payments seem to be gifts. If these are coincidences, we now have a chain of five coincidences. Simple coincidence is defined as the intriguing idea that two unexpected events did not happen by chance but share a hidden link or meaning. In this case we have five apparent coincidences in concurrence which strongly suggests the causal nexus which is missing from simple coincidence. While ordinary coincidences are infrequent, chains of coincidences are almost unknown. Indeed nothing other than a causal link can explain these apparent coincidences which are not due to inexplicable chance but are the result of human intention acting as sufficient cause. Coincidences do happen but they cannot be made to happen.

Explaining that causal link would expose how the ledger and the NLI note are related. If both were written by one person then the first written acted to bring about the other as cause produces effect. But they don’t record the same facts; the ledger records payment to Corbally while the NLI note records payment to Millar. It is necessary to determine which was written first.

Since the NLI note was indeed written by Casement it follows that the ledger entry was written by a second person, by someone other than Casement and is, therefore, a forgery.

If the ledger precedes the NLI note in time we must explain why the diarist recorded payment to Corbally but soon after contradicted that by recording the payment of an identical sum to Millar. If the ledger entry was written after the NLI note, the above contradiction is eliminated but a second contradiction appears with the references to Corbally and the motorcycle which are not present in the earlier NLI note and which contradict it. This fact clearly shows there is a double contradiction afflicting the documents regardless of which was written first. Either sequence produces contradiction which signals we have made a hidden assumption which is responsible for the contradictions. That prior assumption is that the two records were written by one person. As soon as we consider that the records were written by two persons, not by one, the contradictions are eliminated. Since the NLI note was indeed written by Casement it follows that the ledger entry was written by a second person, by someone other than Casement and is, therefore, a forgery. In short, Casement’s authentic record of payment to Millar is a de facto negation of the alleged payment to Corbally.

It was the most ardent forgery denier, Jeffrey Dudgeon MBE, who revealed the vital evidence that led to this proof and it was a most supreme irony that he did so by concealing that evidence too late.

It was the most influential biographer Brian Inglis who in 1973 wrote “(and if one was forged, all of them were) …” – the common law principle falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus. Therefore it can now be stated with categorical certainty that all of the Black Diaries are forgeries and that this ultimately simple proof is irrefutable and conclusive. Two aspects add charm to this proof – its disarming simplicity and its debt to a crusader for authenticity without whom it might never have come to light. Let us give the devil his due and grant that it was the most ardent forgery denier, Jeffrey Dudgeon MBE, who revealed the vital evidence that led to this proof and it was a most supreme irony that he did so by concealing that evidence too late.

Village magazine, 26/4/24

Response to ‘The Devil & Mr. Casement’

In late April The Devil & Mr Casement was published online by Village magazine. In the long Casement saga this was a unique event which in a sane world ought to have terminated the controversy over the diaries. For the first time a logically necessary proof of forgery appeared in the public domain. Logical necessity signifies that the conclusion cannot be otherwise because it is determined by the premises. Thus this kind of proof differs from the more familiar proof based on the calculus of probabilities – the conclusion from circumstantial evidence judged beyond all reasonable doubt where no alternative seems probable. The apodeictic proof allows no option whereas a circumstantial proof can be challenged by reinterpretation of evidence or by new evidence.

The online article rapidly gathered interest and has by now attracted over one thousand visitors. Upon publication some congratulations were received but the negative responses were more interesting because they demonstrate that we do not dwell in a sane world nor are we logical creatures. When these circumstances are considered in the wholly toxic context of the diaries where stupidity, ignorance, complicity and fear condition attitudes, we can anticipate some creative denial. It becomes clear that for some people no proof of any kind would be sufficient and that they adhere to authenticity as did the early Christians adhere to their faith as they entered the arena. For these faithful, authenticity does not rest on evidence, on probability or on logic but rests rather on an invisible structure of deep-rooted beliefs and emotions which are impervious to change or modification and which constitute the psychic architecture of that individual; in short it rests on dogma.

Comment from Professor Kearns of Maynooth came with a condition that his remark was not for publication and that he did “not wish to add to any public comments on your article”. This is an echo of Lucy McDiarmid’s reaction to learning of the forgery of the 1957 poem The Nameless One. She too undertook not to comment publicly on the diaries. In essence, Kearns attempted weakly to insinuate that the NLI note does not mean what it seems to mean but the alleged ambiguity is so contrived it did not even convince Kearns – hence not for publication.

Historian Michael Laffan wrote “I don’t wish to become involved in the controversy, so I decline your invitation to write a comment.” This ‘no comment’ explains nothing least of all why he does not wish to be involved; in 2021 he stated “But I still believe that the diaries are probably genuine.” He then added “I make no claims to expertise in the question of the diaries …” which confirms that he has done no primary source research. He is therefore a historian who is not able to recognize propaganda and thus believes the propaganda instead.

Barrister and TD James O’Callaghan wrote that as a politician he was not qualified to comment on the proof. He added that competence to comment on a matter of logical necessity belongs exclusively to historians. These would be the same ‘no comment’ historians who have done no research because they prefer propaganda.

Cowardice and evasion are very common phenomena in the diaries question.

Barrister John McGuiggan’s reaction to the article contained over 1,100 words and can also be described as evasive since not one word engaged with or challenged the proof. He was obsessively concerned with finding relevance in the forgery of the Hitler diaries. He also expanded on what such an extensive forgery would involve and implied that HM government had no motive or even time for the task. Since McGuiggan has elsewhere referred to Dudgeon’s book as definitive it is obvious he has not done any research of his own and he has certainly not read Anatomy of a lie although he claims to be a “well-read” amateur historian. He closed with his only reference to the proof: “You ask us to believe Mr. Hyde, that your new two-stroke motorbike theory of forgery is a major Triumph in the forgery controversy. It is not. It carries very little weight.” Eventually his full ‘explanation’ arrived.

According to McGuiggan the argument “… has no intellectual weight, no logical weight , no evidential weight an [sic] no historical weight. It is founded on the extraordinary assertion that the entry in Casement’s 1911 Cash ledger: ‘Cyril Corbally and his motor bike for Millar £25.0.00’. is “suspicious” because it “contains too much information” in fact , according to Mr. Hyde, “four times as much as necessary”. (I have struggled to correct McGuiggan’s creative punctuation.)

To avoid challenging the proof directly, McGuiggan presents a fake challenge – a decoy. He alleges that the entire proof is “founded on the extraordinary assertion” that the ledger reference to Corbally is described as ‘suspect’ and as an ‘artifice’. His claim is cunning nonsense. Nothing is founded on that description. Indeed one may easily hold the ledger sentence to be innocuous without this affecting the contradictory evidence in the documents. To support this deceit McGuiggan then presents eleven words enclosed with double inverted commas as purported quotations from the Village article. This constitutes false attribution because those words do not appear in the article. This intentional misrepresentation is dishonest and always indicates absence of argument. McGuiggan’s failure to engage honestly with the evidence and the proof published in Village is a result of his faith in Dudgeon.

Last reaction received came from the devil himself, Jeffrey Dudgeon. His response here has been shortened by 139 words which do not refer to the proof article. His full response can be found in the print edition of Village.

‘The delay in replying is largely due to putting the finishing touches to my 4th edition: The Complete Black Diaries.

My silence is not consent in matters Casement (Italian tags notwithstanding) so I will be vocal if told Village would publish my response. The magazine chose previously not to regarding a letter I submitted on your Sidney Clipperton story.

You wrote in Village: ‘Here is the sentence which Dudgeon deleted from his third edition of 2019. “It is possible that Millar bought the motor bike from Corbally and that Casement was repaying him as a separate note listing expenditure simply reads ‘Millar 25.0.0′”. This sentence published by Dudgeon from 2002 to 2019 fatally compromises his overall endeavour to persuade us of authenticity. It signifies serious confusion; he does not know who paid for Millar’s motorcycle. It also signifies that he admits the possibility that Casement did not pay Corbally as alleged in the ledger which therefore would be a forgery.

The reason why I dropped the ‘possible’ option of Millar buying the motor bike directly from Cyril Corbally, rather than Casement paying him, was due to you and Tim O’Sullivan discovering that Corbally was the manager of a golf club in Essex. That led me to ascertain he was Lady ffrench’s brother, Corbally being her maiden name.

Plainly the sale involved the ffrenchs and was processed in England although Millar re-registered the bike in Essex as he was obliged to do.

There is no contradiction in Casement recording the £25 he spent against Corbally and against Millar in different places.

The money to Corbally was payment for a gift to Millar.

Actually, I realise now the 3 June entry is even more confirmatory of Casement paying Corbally.

My 3rd edition change could not in a hundred years be regarded as something that “fatally compromises [my] overall endeavour”.

I can expand on all this and more in a response in Village once given a word length.’

There are three essential points in his confused 464 word reaction which is compromised by lack of evidence and logic.

1 – Dudgeon deleted the compromising sentence upon discovering “Corbally was the manager of a golf club… That led me to ascertain he was Lady ffrench’s brother …”

2 – Concerning the motorbike transaction he states “Plainly the sale involved the ffrenchs …” If ‘Plainly’ means obviously, Dudgeon does not explain why Lady ffrench would get involved in selling a second-hand motor bike.

3 – Dudgeon denies the contradiction at the core of the proof; “There is no contradiction in Casement recording the £25 he spent against Corbally and against Millar in different places.” The two different places are the ledger, a disputed document of unknown provenance, and the NLI note accepted by Dudgeon as a true record of Casement’s payments to various persons including Millar. Dudgeon’s confirmation that Casement paid Millar logically excludes that he also paid Corbally.

There is no evidence that Casement wrote the ledger but there is conclusive evidence that he wrote the NLI note. Dudgeon accepts that evidence. For Dudgeon, however, the statements are not in contradiction; he says that they record the same thing – a single payment – in two places. But this is evidently untrue since they refer to two distinct recipients and for 17 years Dudgeon himself openly accepted in his book that he did not know who had paid Corbally thereby casting doubt on the ledger as a true document. Now when he clearly sees he is trapped by a proof based on rigorous logical necessity, he launches into further desperate guesswork hoping to rescue a conjecture which failed decades ago. This rescue operation requires yet another vain speculation; “Plainly the sale involved the ffrenchs …” If ‘plainly’ means obviously, this involvement was not obvious to Dudgeon for the last 22 years and therefore only became ‘obvious’ to him after reading the proof in late April this year.

But it is now too late for Dudgeon to rescue his position which he himself compromised many years ago. With that fatal sentence ‘It is possible that Millar bought the motor bike

from Corbally …’ one critical observer commented “He has hanged himself.”

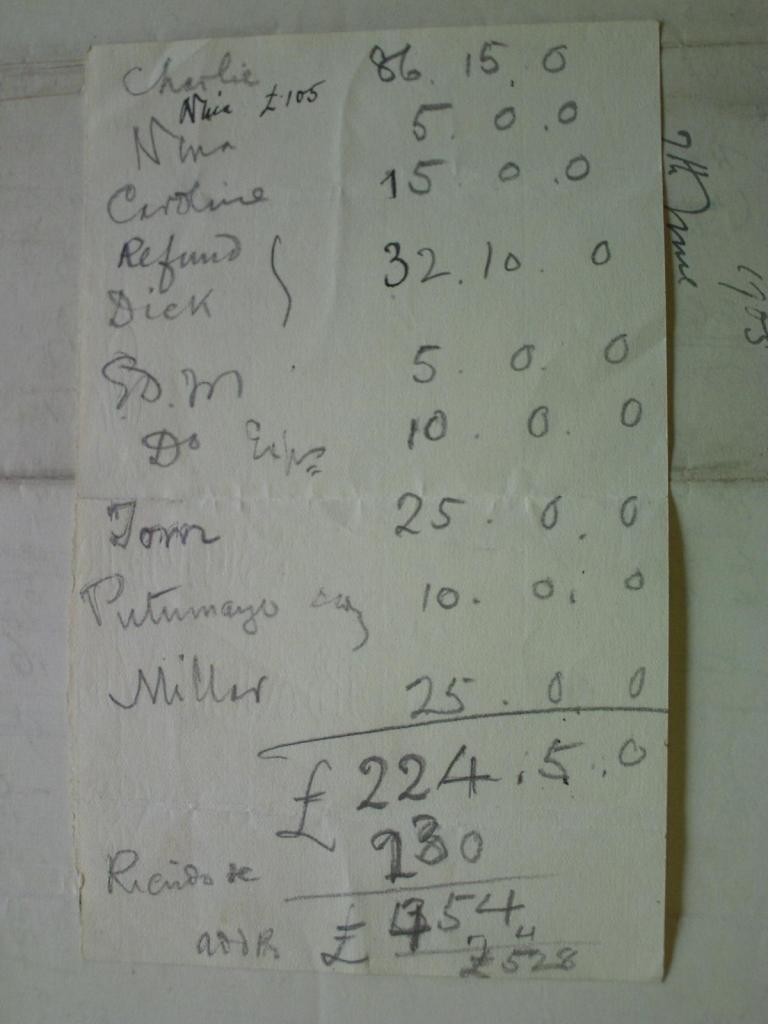

Photo of NLI MS 15,138/1/12

The payments listed are undated but cover the period before Casement left for the Putumayo in mid-August 1911. It is not known if the Millar payment was a gift or a loan. Conspicuously missing is any record of a payment to Corbally; also missing are the used cheque-book stubs recording the listed payments in the post April period although fourteen used cheque-books for before April are in the file. If as alleged in the ledger Casement had paid Corbally £25 on 3rd June, it must be explained why it is not recorded among these payments made in the same period.

These payments were made at various times from May to July but the nine main payments listed seem to have been written on a single occasion on or after 31st July. External evidence confirms the refund to Dick Morten was made in 2 parts, first on 28 April and second on 31st July. External evidence shows that two loans to Caroline were made by cheque in April and early July. The purpose of the exercise was not to record payments already noted on the cheque stubs but to calculate the total amount. Notes on the reverse confirm this. It cannot be determined if the recorded sequence of payments represents a chronological sequence because the corresponding cheque stubs are missing from the file. Certainly this file was examined by MI5, most probably by Frank Hall. The stubs would have verified the dates of the Millar payment and that of the alleged Corbally payment. The absence of a stub recording a Corbally payment would be sufficient and necessary motive for destruction of that used cheque-book. No other motive has credibility.

Paul Hyde

Irish Political Review (September 2024)

Virtual Casement

That Inglis’ influential 1973 biography is both dishonest and negationist has been demonstrated and very few would now attempt to defend it. One of those very few, however, is the self-published Belfast author Jeffrey Dudgeon, a long-term forgery denier, veteran researcher and author of what is perhaps the longest and most sophistical Casement book. One might ask; is he more misleading than Inglis? In terms of both quantity and quality the answer must be yes. Whereas Inglis’ dishonesty focused in his biography mostly on the diaries and was used economically and with just enough subtlety to avoid scrutiny, Dudgeon’s sophistry permeates his entire opus so that his book is generously saturated with fiction. While Inglis concealed his deceits quite effectively, the sheer quantity of Dudgeon’s sophistry means that concealment can only be achieved by rendering his narrative impenetrable and therefore doubt resistant. Certainly his book contains uncontested and verified facts but while these are banal and inconsequential they nonetheless serve to disguise his speculations as ‘virtual facts’.

My own early attempts to read Dudgeon’s book were frustrated because it is uncontrollably speculative and devised to be self-verifying. That such confusing, illogical, syntactically disturbed writing would be taken seriously seemed to me improbable but I was wrong. I did not then understand that the evasions, allusions, conflicting registers, non-sequiturs, wiles, feints, curious locutions and various demotic frothings are the essential ingredients which constitute the impenetrable mask of sophistry. Today Dudgeon’s book is taken seriously and by many vulnerable people who have done no research of any kind; having digested Inglis they have no critical perspective and therefore cannot understand that Dudgeon’s Casement is entirely ‘virtual’.

It is when we focus on this fictional Casement in Dudgeon’s book that we begin to ‘appreciate’ the difficulties Dudgeon had to overcome so that his book might become genuinely influential. In short, Dudgeon’s Casement is an unpleasant sexually-obsessed character driven by incessant carnal desire who daily frequents prostitutes, indifferent to health risks and without moral scruples. Despite this, Dudgeon seems to approve and perhaps admire the sexual behaviour of his fictitious Casement and he does not seem disturbed either by the relentless promiscuity or by the fact that many of the sexual encounters related are with adolescent males and therefore his imaginary Casement is a pederast. Certainly readers will search in vain for any critical remark by Dudgeon regarding either pederasty or promiscuity.

‘He did it often. He did it in public places. He did it with young men and with boys. He was promiscuous and he did not worry about laws and sexual morals.’

Position 15869 Kindle.

But there is another aspect which ought to cause Dudgeon concern since it is a matter of real concern to anyone with a claim to moral judgment in sexual behaviour. The overwhelming majority, perhaps as high as 95% of the fictitious sexual encounters are commercial transactions – they are paid for. This prostitution does not concern the fictitious Casement any more than it concerns Dudgeon and indeed the term prostitute or prostitution appears only five times in his 800 page book. At no point does Dudgeon express disapproval of prostitution, not even indirectly. Indeed, he does not need to disapprove because it is a measure of his sophistry that he denies both that the payments are made for sexual favours and that the partners are prostitutes. Dudgeon’s revision informs us the payments are not payments but are gifts and the sexual favours are given eagerly without desire for monetary gain.

‘The boys are not prostitutes, indeed those on the street are usually eager, but they have self respect…’ while Dudgeon’s Casement is ‘…aware that it would be bad form not to offer a present.’ Position 9899 Kindle edition.

‘Casement enjoyed himself sexually, displaying little or no guilt and certainly no shame … an early exemplar of what is now standard sexual behaviour.’

Position 372 Kindle edition.

Thus Dudgeon would have us believe these transactions are not commercial but are part of an ongoing program to facilitate the redistribution of wealth via gifts from the well-off to the deserving poor. This ‘explanation’ leads to the following equation; the potent sexual appetite of Dudgeon’s Casement is stimulated further by empathy for the poor and his evident voracity stems also from an uncontrollable generosity. However, Dudgeon does not explain how his Casement is able to distinguish in a red light zone between the real prostitutes and the good-natured poor who are willing to perform gratis.

In this way Dudgeon seeks to avoid what is indeed a predicament in his portrayal of the imaginary Casement. On one hand the diaries impose on him a predatory, promiscuous pederast and habitual client of young prostitutes while his priority is somehow to present his Casement as an acceptable homosexual. The Casement depicted in the diaries would be unacceptable to most of his readers not least because the portrait is so obviously homophobic. Therefore Dudgeon feigns not to notice this homophobia (the original motive for producing the diaries) and he boldly informs us such predatory indulgence is now ‘standard sexual behaviour’. By ‘standard’ he can only mean sexual behaviour without moral parameters is normal and widely accepted. Dudgeon may inhabit this world with no moral dimensions but it is highly improbable that many of his readers approve of promiscuous pederasty and prostitution. It cannot be determined if Dudgeon recommends the prostitution and pederasty narrated in the diaries but his failure to condemn invites readers to infer approval.

Prostitution is always problematical because it is often linked to criminal activity, to poverty, squalor and exploitation, to slavery, to trafficking in drugs and people. Even when tolerated and regulated, prostitution reduces what should be a meaningful and spontaneous emotional/physical event into a monetary transaction in which one party purchases ‘a service’ from a stranger who needs money. It is this disparity in wealth which reveals the predatory nature of most prostitution. Thus it eliminates the affection in human sex leaving the act void of emotional meaning.

There is another dimension to the virtual Casement invented in the diaries a century ago but still with us today although greatly revalued so that today’s Casement is widely admired for precisely the behaviour which condemned him in 1916. That disturbed behaviour as reported in the diaries and especially in the 1911 diary would condemn him in the eyes of many homosexuals today as being symptomatic of a degenerative and addictive illness. In short, the portrait is undeniably homophobic and utterly negative. Among those who today believe the portrait is Casement’s self portrait some must have actually read the 1911 diary yet they are insensitive to the extreme homophobia and seem to find the portrait credible and inoffensive. It is difficult to believe they condone or understand the lecherous and priapic sex addict they encounter in the diary. Moreover, those readers also appear to endorse the prostitution and pederasty which is depicted and they do so in the name of what they believe to be tolerance and sexual liberation. Blind to the evident homophobia in the diaries and above all determined to display their tolerance, they are incapable of understanding how they have been manipulated into abandoning all critical perspective on human behaviour.

Dudgeon’s reliance on misleading falsehood is not confined to his own book and in a review of Anatomy of a lie published in the Irish Literary Supplement this year several clear examples can be found. On several points he has intentionally misrepresented my arguments in ways which are reminiscent of that master deceiver Brian Inglis.

False attribution is a favoured defensive tactic of the artists of negationism and propaganda. Dudgeon is a master of this technique which is predicated on the reader being poorly informed. An egregious example is his preposterous claim that I defend the character of Casement’s servant Christensen since I dispute the allegations of his treachery to Casement. Like Dudgeon, I know nothing about Christensen’s character but there is no documentary evidence of such treachery in 1914-15 as demonstrated in pages 183-6 of Anatomy of a lie. The purported betrayal was invented in 1973 by Inglis who provided no evidence. Christensen perhaps was an unsavoury person but the Foreign Office documents clearly show that he did not betray Casement despite many opportunities to do so.

Dudgeon also misrepresents my argument concerning the absence of independent evidence for the material existence of the bound diaries in 1916. Dudgeon claims that I assert ‘the diaries first came into existence when they were typed by Scotland Yard’. This is nonsense. It is undisputed that the typescripts were prepared by the Metropolitan police. The police typescripts are not diaries. Dudgeon then abandons his ill-conceived position with the following outlandish proposal; ‘a corps of male typers’ with detailed knowledge of the Congo, the Amazon and of homosexuality and the literary gifts of Conrad, Conan Doyle and Rider Haggard.’ This feverish nonsense is then put aside as he falls back on the official version of provenance without telling us that his preferred version is one of seven conflicting versions provided by HM officials. Yet to refute my argument he has only to produce independent witness testimony. He cannot do so because there is none.

Elsewhere he claims that I ‘argue against the many’ who believe Casement’s luggage was seized in late 1914 or early 1915. His claim is utterly false; I argue that the trunks were seized at that time and that no incriminating diaries were found then or later. Dudgeon attributes to me an incomprehensible distorted reasoning of his own invention. He does this by confounding yet again the typescripts and the bound diaries. I argue that silence about the luggage contents in 1914-15 is overpowering evidence that no incriminating diaries were ever found.

Elsewhere referring to the 1957 forgery of The Nameless One, Dudgeon claims ‘Frank MacDermot … is accused of faking poetry in cahoots with Unionist MP Montgomery Hyde.’ I do not accuse them of composing the poem. The documents show that MacDermot supplied the typed text to The Sunday Times and that Montgomery Hyde published it alleging falsely that the original manuscript was held in the National Library of Ireland.

Dudgeon claims that the US ambassador was shown the bound diaries in 1916. Dudgeon knows very well the ambassador was shown police typescripts and received two photographs of typescripts as verified by Home Office document HO144/23481. That he will risk stating as true something he knows is false indicates that Dudgeon has lost faith in his own project.

For his review of Anatomy of a lie Dudgeon was specifically invited to comment on the unknown provenance of the diaries, the absence of independent testimony and the role of Inglis. He ignored provenance and failed to give independent testimony to prove the existence of the bound diaries in 1916. He attempted to defend Inglis whose extensive mendacity has been exposed. His defence consisted of denying intent to deceive by claiming Inglis ‘was not always careful with references’. Thus Dudgeon describes Inglis’ calculated duplicity as a kind of clerical carelessness. Unable to convincingly defend Inglis, Dudgeon tries weak rhetoric ‘… which writer gets every transcription right?’ He has nothing to say about the omissions, selective framing, altered documents, false dates and attributions, insinuation and multiple lies which have been exposed.

Dudgeon’s refusal to admit Inglis’ dishonesty makes him complicit in the cover-up which began in 1973. Since the duplicity has now been exposed, authenticity belief requires a cognitive dissonance allowing one to ignore the significance of Inglis’ deceptions. Dudgeon may believe in authenticity but clearly Inglis did not. It is a fact that the consensus for authenticity was created by Inglis’ biography decades ago. Since his multiple deceits have been exposed, no honest person can believe the diaries are authentic. To do so is to believe that lies are true.

© Paul R. Hyde, April 2024. (Amazon review of Dudgeon book, 22 August 2024)